We take a deep dive into recent Australian public market transactions and put reverse break fees under the microscope.

IN BRIEF

|

Australian practice

Reverse break fees are used in control transactions to require the bidder to pay the target a fee if an event occurs (which is usually in the bidder’s control) which leads to the transaction not proceeding, for example, a failure to obtain a regulatory approval or financing failure. Importantly, a reverse break fee is a useful tool for targets to increase deal certainty - by creating a financial disincentive for bidders to walk away from the transaction.

Since 1 July 2015, 154 successful transactions involving ASX-listed targets have been announced. One quarter (39) of those transactions featured reverse break fees. Of those deals, reverse break fees represented approximately 1% of equity value on average (matching the Takeovers Panel’s 1% guideline on break fees in general). This is far lower than US practice, where reverse break fees represented 6% of equity value on average over a similar time period.

Although reverse break fees are more common by sheer number on smaller transactions (perhaps reflective of the risk profiles of bidders in those transactions), the data shows that equity value is not determinative of whether a reverse break fee will feature in a transaction.

RBF usage in announced successful deals by equity value (FY16 – current)

The reverse break fee triggers differ from deal to deal, but from our analysis the top 3 triggers are:

- material breach (32 instances or 82% of deals where there was a reverse break fee);

- financing failure (12 instances or 32% of deals where there was a reverse break fee); and

- bidder changes their recommendation to its own shareholders (10 instances or 26% of deals where there was a reverse break fee).

If we look at the top 3 common triggers in each financial year, we find that the use of triggers has remained consistent over the period.

| Financial Year | Top 3 triggers |

|---|---|

| 2016 |

|

| 2017 |

|

| 2018 |

|

| 2019 |

|

We found that it is common for reverse break fees to act as a cap on the bidder’s liability (25 instances or 64% of deals where there was a reverse break fee). Where that is agreed, the target is accepting that it cannot sue for damages, even if the bidder is in breach of the agreement.

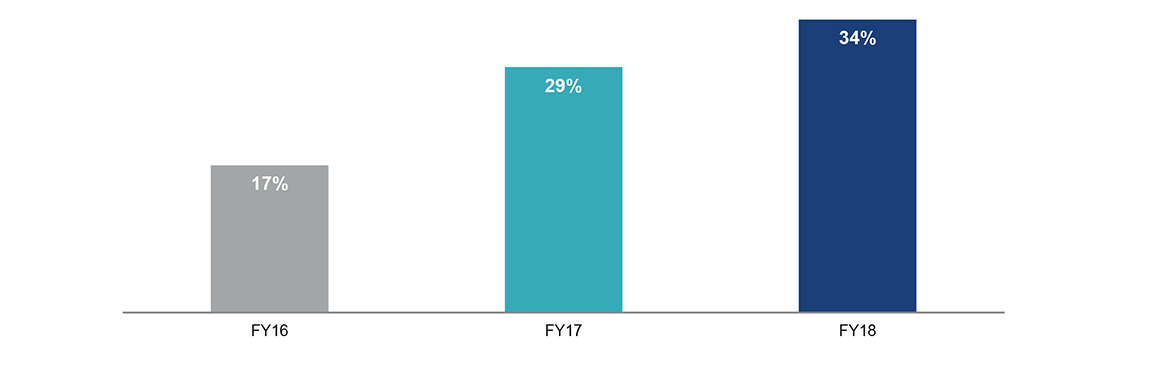

The incidence of reverse break fees is increasing. Our analysis shows that reverse break fees are increasing as a proportion of all successful Australian public market deals in each complete financial year since FY16.

Use of reverse break fees in Australian public M&A

Recent case studies

Looking at the latest transactions that have used reverse break fees may indicate what to expect in the future.

Healthscope

The reverse break fee negotiated in Healthscope’s proposed $4.4 billion acquisition by Brookfield by way of scheme of arrangement and simultaneous off-market takeover bid is a cutting edge example for the Australian market. Of note, however, is that such a reverse break fee would be fairly standard in the US.

The Healthscope transaction featured a two tiered reverse break fee (itself unusual in our market). The first tier involved a $129 million reverse break fee representing 3% of equity value – one of the largest reverse break fees achieved in Australian corporate history. The reverse break fee under the first tier is triggered upon Brookfield’s material breach. This was essentially intended to cover financing risk.

The second tier involved a $50 million reverse break fee (approximately 1.2% of equity value). The second tier would be triggered if FIRB approval was not obtained by the buyers of the approximately $2.1 billion sale of 22 freehold properties that Healthscope had agreed to sell as part of the Brookfield transaction to Medical Properties Trust and NorthWest. To our knowledge, this is one of only 3 instances where a target has negotiated a reverse break fee payable upon a failure to obtain a regulatory approval since FY16.

The reverse break fees acted as a cap on Brookfield’s liability.

The significance of the reverse break fees negotiated on the Healthscope transaction is that both tiers exceed the Takeovers Panel’s 1% guideline on break fees. The 1% guideline is based on setting a fee which is not going to deter competing bidders. That consideration does not apply when it is the bidder who must pay the fee. Therefore, a reverse break fee is not limited by the Panel’s guideline.

DuluxGroup

Nippon Paint’s proposed acquisition of DuluxGroup is another recent transaction which has employed a reverse break fee, in this instance a standard reverse break fee structure was used. The quantum of the reverse break fee was approximately $38 million, representing 1% of equity value. The sole trigger for payment was Nippon Paint’s material breach. As is common, the reverse break fee acted as a cap on Nippon Paint’s liability.

The reverse break fee employed on the DuluxGroup transaction is an example of the most vanilla reverse break fee structure in the Australian market.

Conclusion

Although the incidence of reverse break fees has trended upwards since FY16, the structure of them being the triggers and quantum as a proportion of equity value has remained consistent. It will be interesting to see whether the reverse break fee structure in the Healthscope transaction will set a new benchmark for public market transactions in Australia, bringing the market a little closer to standard US practice.

Legal Notice

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2024