Central to the response of the international community to the global financial crisis was a move to strengthen international regulatory standards and to improve cooperation and coordination amongst regulators. A question for the decade ahead is how much of that global approach will survive?

A focus on Australia is below.

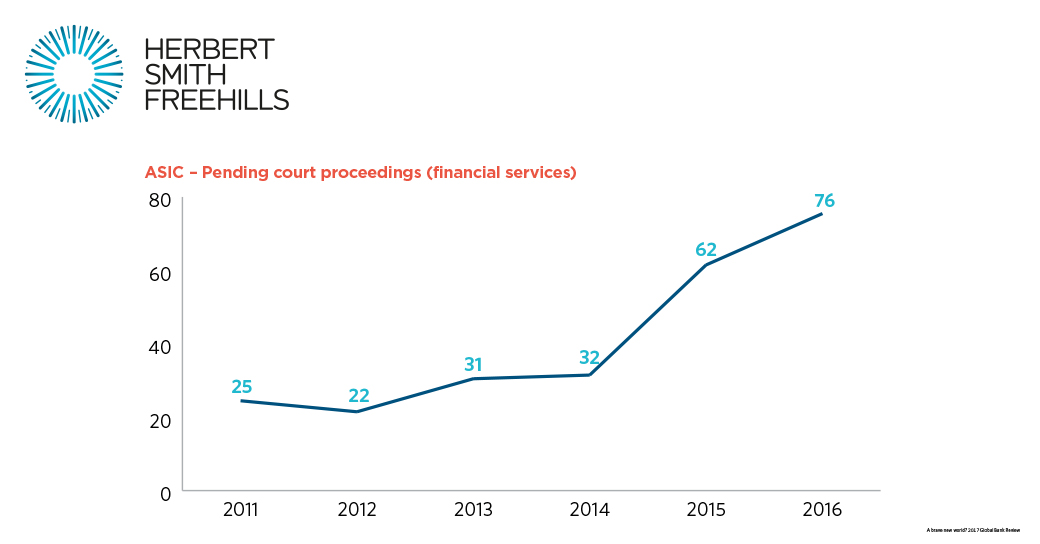

The past two years have seen an unprecedented wave of litigation by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) against the financial services sector, including the major banks. Banks are also being served with an avalanche of notices to produce documents and answer long lists of detailed questions. Even when an investigation does not warrant court proceedings, ASIC is increasingly insisting on “enforceable undertakings” with a substantial “community benefit” payment as the price of peace. Where a particular issue affects more than one bank, ASIC is adopting a divide and conquer strategy – obtaining a concession from one bank and then pressuring the others to do the same.

ASIC has received substantial funding to investigate and prosecute the banks. It may well be that ASIC, in turn, feels it should to deliver a return on that investment.

What is missing from the political debate and, it seems, from ASIC’s strategy, is an accounting of the cost of the strategy of regulation by litigation. Hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent by ASIC (at the expense of taxpayers) and the banks (at the expense of customers and shareholders) dealing with enforcement. And the cost is not just financial. When ASIC and senior management of the banks spend significant amounts of time raking over the coals of the past, they are left with less time to focus on improving customer outcomes in the present and future.

To be clear, ASIC enforcement activity has an important role to play in regulating financial markets. If misconduct is not punished, it is encouraged. However, ASIC’s track record of identifying institutional, as opposed to individual, misconduct in the financial services industry is patchy at best.

More significantly, much of the litigation commenced by ASIC does not truly concern misconduct but arises from genuinely held but differing interpretations of the relevant law. After one of its most significant court losses, against Citigroup in 2007, ASIC said that where it “feels that clarification of the law by a court is important, it will as a matter of policy, commence proceedings”.

It is difficult to consider that litigation is the most efficient and effective way to clarify the law. If ASIC was prepared to reserve investigations and litigation for cases of suspected misconduct and to engage in dialogue with the banks as a whole about industry issues and legal uncertainty, customer outcomes for the future would be improved more quickly and cost-effectively.

This article is an excerpt from “Global financial regulation – the decade ahead”, currently appearing in the Global Bank Review 2017 publication. Other articles in this series include:

- Part 1: United States

- Part 2: Europe

- Part 3: Asia-Pacific

To download the complete version of this article click here.

Legal Notice

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2024