Bis Industries’ ground-breaking creditors’ schemes of arrangement facilitated the restructure of A$1.2 billion of debt and transferred ownership of the Bis Industries group to its lenders.

Executive summary

The restructuring of the Bis Industries group (the BIS Group) was one of the most significant and complex restructurings in the Australian market in 2017. It involved a number of ground-breaking elements not seen before in creditors’ schemes, including: (1) the use of the scheme process to alter the consent thresholds for subsequently amending key finance documents (facilitating a subsequent debt-for-equity swap without the need for a further scheme); and (2) the schemes acting as an initial ‘stabilising step’, without directly implementing the subsequent debt-for-equity swap.

The BIS restructuring

BIS Group pre-restructure

Bis Industries is an Australia-based group in the resources logistics and materials handling market.

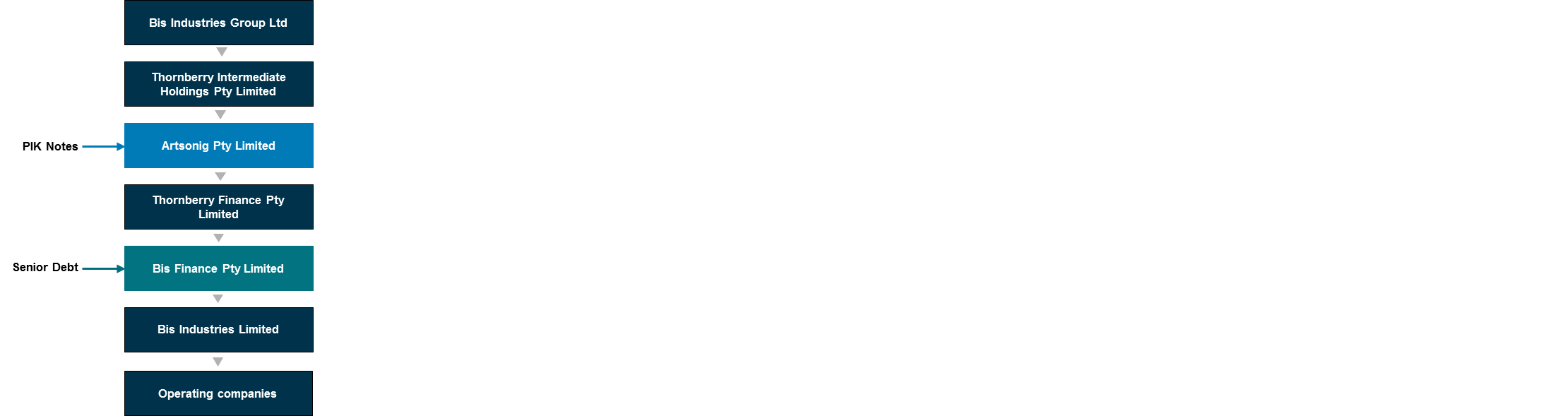

Prior to the restructuring, BIS Industries Limited and the other operating companies of the BIS Group were privately owned through a chain of holding companies, including Artsonig Pty Ltd (Artsonig), Thornberry Finance Pty Ltd (Thornberry) and Bis Finance Pty Ltd (Bis Finance). This is illustrated in the simplified structure chart below.

The total pre-restructure debt of the BIS Group was approximately A$1.2 billion, consisting primarily of:

- senior debt of approximately A$700 million (as at 31 October 2017) owed by Bis Finance to lenders under a syndicated facilities agreement (the SFA) and related hedging documents. This debt was guaranteed by Thornberry and the operating companies, and secured by security over all the assets of Bis Finance, Thornberry and the Australian operating companies. The senior debt all ranked equally under the finance documents, with the exception of the A1 facility under the SFA (approx A$32.5m as at 31 October 2017) which had ‘super senior’ status; and

- payment-in-kind (PIK) debt of approximately US$380 million (including capitalised interest, as at 31 October 2017) owed by Artsonig to noteholders under a New York-law governed notes indenture (the PIK Indenture). The PIK notes were structurally subordinated to the senior debt and were not guaranteed or secured.

The independent expert’s report produced for the purposes of the schemes demonstrated that the enterprise value of the BIS Group was significantly below the value of the senior secured debt.

The restructuring stages

In July 2017, agreement was reached between the BIS Group, a senior lender steering committee, the majority of the PIK noteholders and the private equity owner on a restructuring of the BIS Group.

The restructuring occurred in two key stages:

Stage 1: transfer of ownership to senior creditors

The first stage of the restructuring involved Thornberry transferring ownership of the shares of Bis Finance (and thereby the operating subsidiaries) to a senior creditor owned Cayman Islands vehicle, Bis Industries Holdings Limited (Newco), in exchange for the release of Thornberry’s guarantee and security obligations.

This initial stabilising step was intended to give confidence to Bis’ counterparties and stakeholders regarding the restructure and future of the group, while allowing time for the details of the recapitalisation of the BIS Group to be agreed and implemented.

It was implemented through a scheme of arrangement between Bis Finance and the senior creditors (the Senior Scheme).

Contemporaneously with the Senior Scheme, a second scheme of arrangement between Artsonig and the PIK noteholders approved the transfer of the Bis Finance shares to Newco under the Senior Scheme, in exchange for the PIK noteholders receiving an entitlement to elect to receive 4% of the shares in Newco upon implementation of the second stage of the restructure (the PIK Scheme).

Neither the senior debt (other than the Thornberry guarantee) nor the PIK notes were compromised during Stage 1. However, the PIK notes were effectively left behind in an empty shell once the transfer of the Bis Finance shares occurred.

Stage 2: recapitalisation

The second stage of the restructuring provided for the recapitalisation of Bis Finance and the operating subsidiaries by way of a debt-for-equity swap in respect of the senior debt.

The recapitalisation involved a reduction of the (non-A1) senior debt from approximately A$700 million to approximately A$238 million in exchange for the senior creditors receiving 96% of the shares in Newco. At the same time, the PIK noteholders were issued with 4% of the shares in Newco.

The super senior A1 facility was not subject to the debt-for-equity swap, and remained outstanding on its existing terms (accordingly, the A1 lenders did not receive any shares in Newco).

Following the restructure

After both Stage 1 and Stage 2 had been completed, the debt of the BIS Group was reduced from approximately A$1.2 billion to approximately A$280 million plus A$38 million of finance leases.

The Schemes of Arrangement

The two schemes of arrangement each comprised a number of elements.

The Senior Scheme

The Senior Scheme was between Bis Finance and the senior creditors (other than the facility A1 lenders, although the facility A1 creditors separately agreed to the restructure).

The Senior Scheme provided for (among other things):

- the transfer by Thornberry of all shares in Bis Finance to Newco;

- the release by the senior security trustee of the guarantee and security granted by Thornberry in respect of the senior debt;

- an interim standstill on creditor enforcement actions under the senior finance documents, and restrictions on the transfer of senior debt until Stage 2 of the restructure occurred; and

- amendments to the consent thresholds under the senior finance documents to allow the Stage 2 recapitalisation to occur without the need for 100% of senior creditor consent (as would have otherwise been required absent the scheme). The amendments allowed ‘super majority beneficiaries’ holding 80% of the senior finance debt to amend the finance documents to take certain actions under, or make future amendments to, the finance documents.

The Senior Scheme was not conditional on the PIK Scheme being approved and implemented.

The PIK Scheme

The PIK Scheme was between Artsonig and the PIK noteholders.

The PIK Scheme provided for (among other things):

- consent by the PIK noteholders to Thornberry transferring all the shares in Bis Finance to Newco (which was owned by the Senior Scheme creditors); and

- an entitlement for PIK noteholders to be issued 4% of the Newco shares upon implementation of Stage 2 of the restructure.

After its approval in Australia, the PIK Scheme was recognised in the US pursuant to Chapter 15 of the US Bankruptcy Code.

Novel features of the transaction

Scheme as an interim ‘stabilising’ step

Creditors’ schemes of arrangement are most commonly used in Australia to carry out a full restructure of a company’s debts, including by adjusting (i.e. reducing) the debt owed by the scheme company to scheme creditors and/or effecting a debt-for-equity swap to transfer ownership or partial ownership of a group or company to the scheme creditors. The use of a creditors’ scheme of arrangement as only the first step in a broader restructuring had not previously occurred in Australia.

The Senior Scheme was only an interim ‘stabilising’ step in the broader restructure and recapitalisation of the BIS Group. It did not itself provide for any reduction in debt owed by Bis Finance to the Senior Scheme creditors and did not effect the debt-for-equity swap that occurred in Stage 2 of the restructure. Rather, the Senior Scheme provided for a standstill in relation to the senior secured debt, and the transfer of the Bis Finance shares to Newco. Whilst the Senior Scheme contemplated and facilitated the ultimate recapitalisation of the group (particularly through the finance document amendment mechanism described below), its approval and implementation did not effect the holistic restructuring nor guarantee that the broader restructuring would occur.

Whilst ‘standstill schemes’ that do no more than implement a standstill have previously been approved by the English courts (e.g. in the restructurings of Metinvest, DTEK Finance and Apcoa Parking), there had not, prior to the BIS Group schemes, been a standstill scheme in Australia. Notwithstanding this, Justice Black of the Supreme Court of New South Wales had no issue with this purpose of the Senior Scheme.

Ultimately, Stage 2 of the restructure occurred one day after implementation of the Senior Scheme, and on the same day as (but after) implementation of the PIK Scheme. However, the two stages of the restructure could have theoretically occurred several months apart. The two-stage approach allowed for greater flexibility in terms of timing of the second stage, in the event that negotiations or other events delayed the recapitalisation.

Finance document amendment mechanism

Another novel feature of the Senior Scheme was the amendment it effected to the security trust deed for the senior finance debt.

This amendment allowed the senior security trustee to effect an assignment of senior debt (other than the A1 facility) from the existing non-A1 lenders and hedge counterparties to Newco (and then a subsequent assignment of the debt to Bis Finance, at which point it was extinguished), on the instruction of ‘super majority beneficiaries’ holding at least 80% of the relevant exposures. In each case any such changes were required to be implemented in the same manner across all relevant beneficiaries. These matters would have otherwise required the agreement of all relevant lenders and hedge counterparties.

This meant that Stage 2 of the restructuring (the debt-for-equity swap) could be done with super majority (80%) consent, and without the need for a further scheme in the event of a hold-out creditor. Structuring the scheme in this way provided greater certainty for Bis Finance and its stakeholders that the subsequent recapitalisation would be completed efficiently.

Normally, material amendments to finance documents such as amendments to the level of debt, repayment timeframes, applicable interest rates, the assignment of debt by obligors and the introduction of new facilities with priority over existing lending would require the consent of all, or all affected, lenders and beneficiaries. A facility agreement will typically set out a fairly standard list of such ‘all lender’ matters in the variations clause.

In this instance, the Senior Scheme did not reduce the consent threshold for all of the ‘all lender’ matters, but only a narrow set of specific amendments, and subject to a number of requirements. The Court, in approving the Senior Scheme, was therefore not granting the super majority beneficiaries unlimited power to amend any aspect of the finance documents. Nonetheless, the amendments were not limited only to implementation of Stage 2 of the restructuring but could be used to effect other changes to the finance documents which were not specifically contemplated at the time the Senior Scheme was approved by creditors and the Court.

A similar amendment was made to the PIK Indenture which allowed further amendments to the PIK Indenture to be effected with the consent of noteholders holding 75% of the principal amount of the outstanding notes. Unlike the senior debt, however, the amendment provisions to the PIK Notes had limited impact in substance, as the PIK Notes were left as claims against an ‘empty shell’.

This is the first time in Australia (or, as far as we are aware, in any scheme of arrangement elsewhere in the world) that a scheme has been used to lower the consent thresholds within finance documents to allow further amendments following implementation of the scheme, in order to facilitate a broader restructuring. It was a particularly novel mechanism because it required the parties, and the Court, to draw a critical distinction between the BIS Group schemes and the numerous cases which have held that schemes of arrangement cannot contain internal amendment mechanisms: that is, a scheme cannot contain a mechanism which allows the scheme itself to be modified after it has been approved by the Court.

However, as noted by Justice Black, the finance document amendment mechanism was not an internal scheme amendment mechanism; it did not provide for the variation of terms of the schemes (rather, they allowed a different mechanism for the amendments of the financial documents). The finance document amendments were accordingly approved by the Court.

Class formation and director appointment rights

One of the features of the Newco articles of association, which were in place prior to the first scheme court hearing, was that a shareholder with more than 17% of the Newco shares from time to time would be entitled to appoint a director to Newco’s board. This right was not a one-off right or limited in time but an enduring right in the articles.

There is no reported precedent for the inclusion of such an enduring appointment right in the governance arrangements of a debt-for-equity swap scheme. For example, the Boart and Nine Entertainment schemes of arrangements provided that certain significant shareholders would have a one-off automatic board appointment right; in contrast, substantial Newco shareholders have a continual right to appoint directors.

In certain circumstances, an enduring director appointment right may create such a difference in rights between creditors that separate creditor classes may need to be formed to vote on a scheme. However in this case, Justice Black stated, ‘I accept that, prima facie, those rights are not of such a magnitude or sufficiently different to create a class composition issue’.

Commentary

The unique features of the BIS Group restructure as set out above illustrate the breadth of what can constitute a ‘compromise or arrangement’ in a creditors’ scheme of arrangement.

Although it had generally been anticipated that ‘standstill schemes’ would be permissible under section 411 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act), particularly given the UK precedents for approving such schemes, the BIS Group schemes have confirmed that Australian schemes do not need to actually restructure debt as part of a scheme itself. In this case, the actual debt restructuring occurred in the second stage following implementation of the schemes. The judgment of the Supreme Court of New South Wales provides support for the proposition that schemes that do no more than provide for a debt standstill, or simply ‘amend and extend’ the debt terms, are also permissible in Australia. Such schemes are, in the authors’ view, plainly permissible and appropriate. Whilst of course it is necessary to show, in each scheme case, that what creditors and the Court are being asked to approve does indeed constitute a ‘compromise or arrangement’ within the meaning of section 411 of the Corporations Act, this case confirms that the compromise or arrangement concepts are broad ones.

The two-stage restructuring gave rise to a separate issue in relation to the PIK Scheme: the PIK Scheme contained compromises in terms of the PIK noteholders’ rights against Artsonig, and in return provided an entitlement to Newco shares should the ultimate restructuring occur. Thus, one of the main benefits for PIK noteholders, being the issuance of Newco shares, was potentially uncertain in that the PIK Scheme itself did not guarantee that those shares would be issued or that the wider restructure would take place (although the PIK Scheme implementation date would not occur until the BIS Group restructure completion date). Nonetheless, the Court accepted that the PIK Scheme involved sufficient ‘give and take’ to constitute an ‘arrangement’ under section 411 of the Corporations Act, demonstrating that this uncertainty did not undermine the principles associated with schemes of arrangement.

The finance document amendment mechanism effected by the Senior Scheme was another ground-breaking feature that extends the scope of what had previously been approved by courts in the context of a creditors’ scheme. The decision on the BIS Group schemes does not alter the principle that schemes themselves cannot be amended after the fact; but it does show that schemes can be used to adjust the amendment provisions within existing contracts such that those contracts can be further amended in the future, without the need to obtain creditor and court approval through an additional scheme. Whilst the finance document amendment mechanism in this case was subject to restrictions, it will be interesting to see the extent to which courts in future will be prepared to approve schemes that lower the consent threshold for subsequent finance document amendments with fewer (or even no) parameters around the changes that can be made.

Conclusion

The Senior Scheme and PIK Scheme, and the BIS Group restructuring more generally, have demonstrated the breadth of what can be achieved through Australian creditors’ schemes of arrangement. They have set the stage for the use of ‘standstill’ (or other interim) schemes of arrangement in Australia. They also illustrate that schemes can be used to effect amendments to finance documents, which in turn facilitate subsequent restructuring steps without the need for a further scheme. We expect that this ground-breaking restructuring will pave the way for further creativity in Australian restructurings.

Herbert Smith Freehills advised the senior secured lenders to the BIS Group in connection with the schemes of arrangement and restructuring process.

Key contacts

Legal Notice

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2024